APPLYING TO MEDICAL SCHOOL: DACA/UNDOCUMENTED STUDENT

Before reading, please take time to acknowledge your resilience and drive that brought you this far. Take the time to acknowledge those who have undergone this journey with you. The medical school application process is daunting and therefore, self-reflection and self-check-ins are of the utmost importance.

I hope this guide can help answer some of your questions and reassure you that you are not alone whilst applying to medical school;

- 200 DACA medical students currently in the U.S.

- A dozen DACA residents (at least)

- AAMC is increasingly recognizing DACA student applicants

FRESHMAN & SOPHOMORE YEAR:

Your first semester is about re-learning how you learn best. College coursework is more rigorous than high school. The focus of your 1st year is to do well in classes and learn about what drives and interests you!

After your 1st year you should walk away with a better idea of what you will be majoring in and have a tentative plan for your pre-medicine coursework.

TO DO:

- Meet your advisor regularly

- Meet with Health Careers office (≥ 1x/semester)

- Tentative 4-Year Schedule

- Get involved in research

- Get involved in clubs

- Healthcare related volunteering (≥200 hours by graduation)

- Service-oriented volunteering (≥100 hours by graduation)

- November/December: Apply to summer internships (see DACA friendly list!)

- Summer after sophomore year: Begin studying for the medical college admissions test (MCAT) with a plan to take it junior year.

NOTE: I HIGHLY advise you meet with your professors, teacher’s assistants, and/or tutors if you are not getting the grades you would like. I recognize not all schools have the same free resource options however I highly encourage you reach out and ask for help.

Not doing so may put you at great disadvantage later on. Freshman and Sophomore years are the time to learn about these resources and improve your grades. Medical schools value improvement when viewing applications. Bad grades in the first two years are not the end of the world but not addressing these early on may lead to suboptimal outcomes.

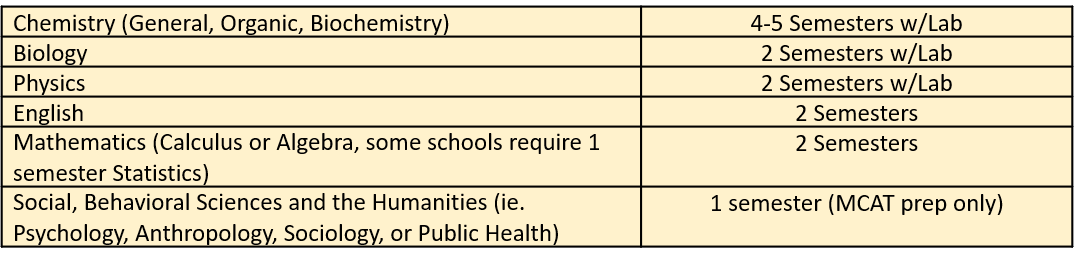

PREMED COURSE WORK*:

*For most schools. To view specific school requirements, please refer to the MSAR

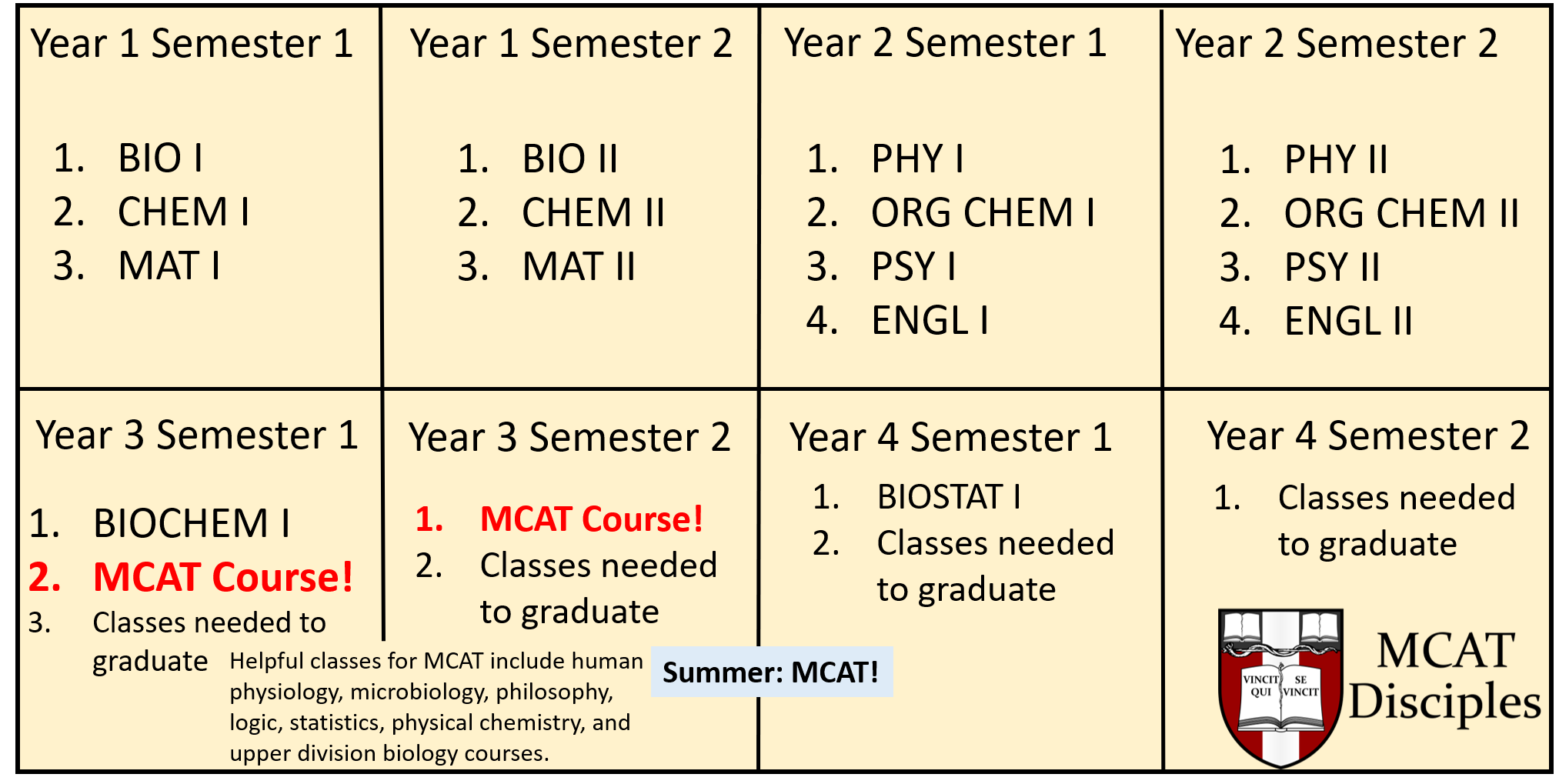

SAMPLE 4-YEAR UNDERGRADUATE COLLEGE SCHEDULING:

JUNIOR YEAR/ SENIOR YEAR:

Junior year you will apply to medical school (if not taking a gap year) and take the MCAT.

TO DO:

- Summer/Fall (before junior year): Study for the MCAT

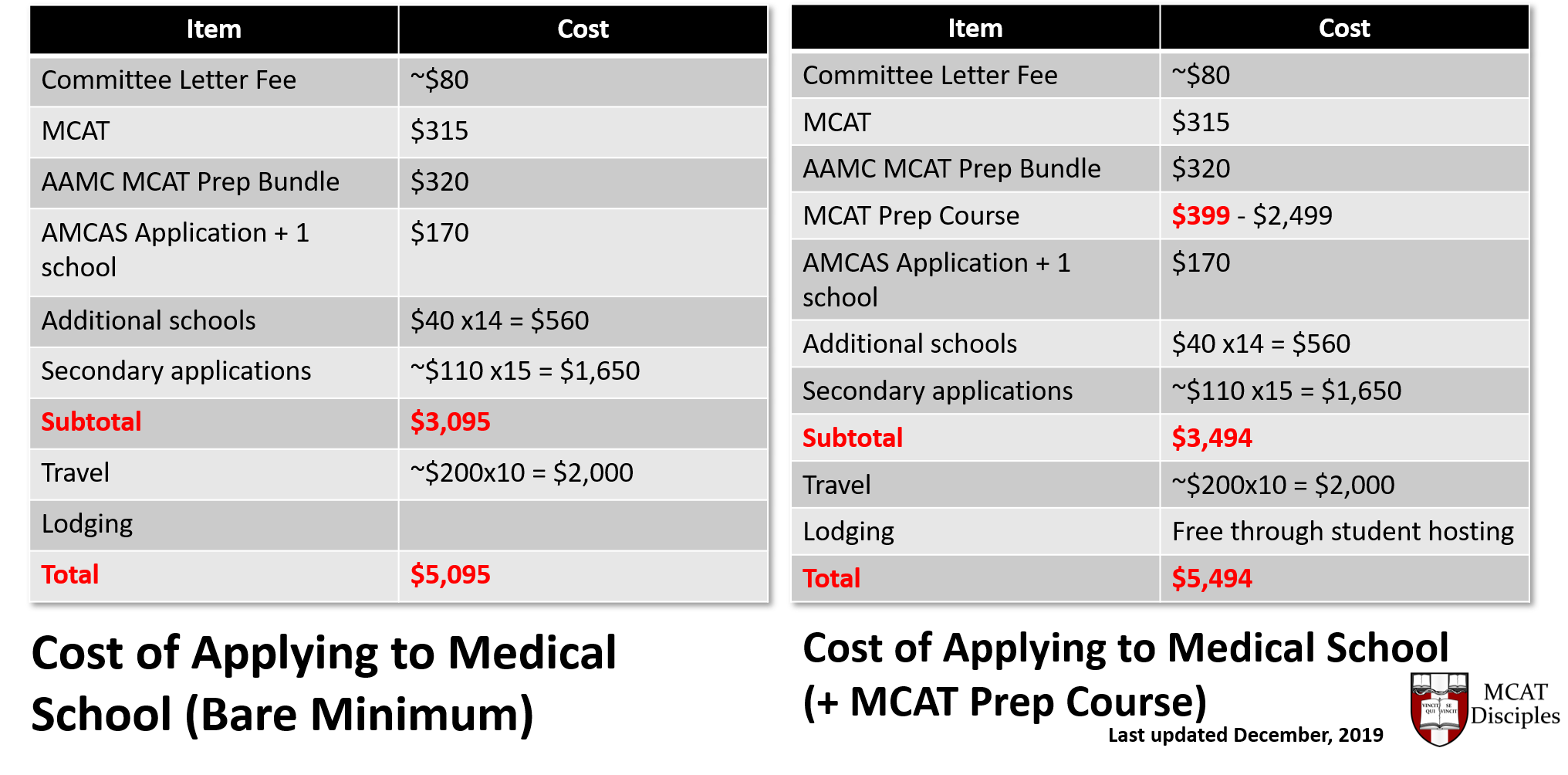

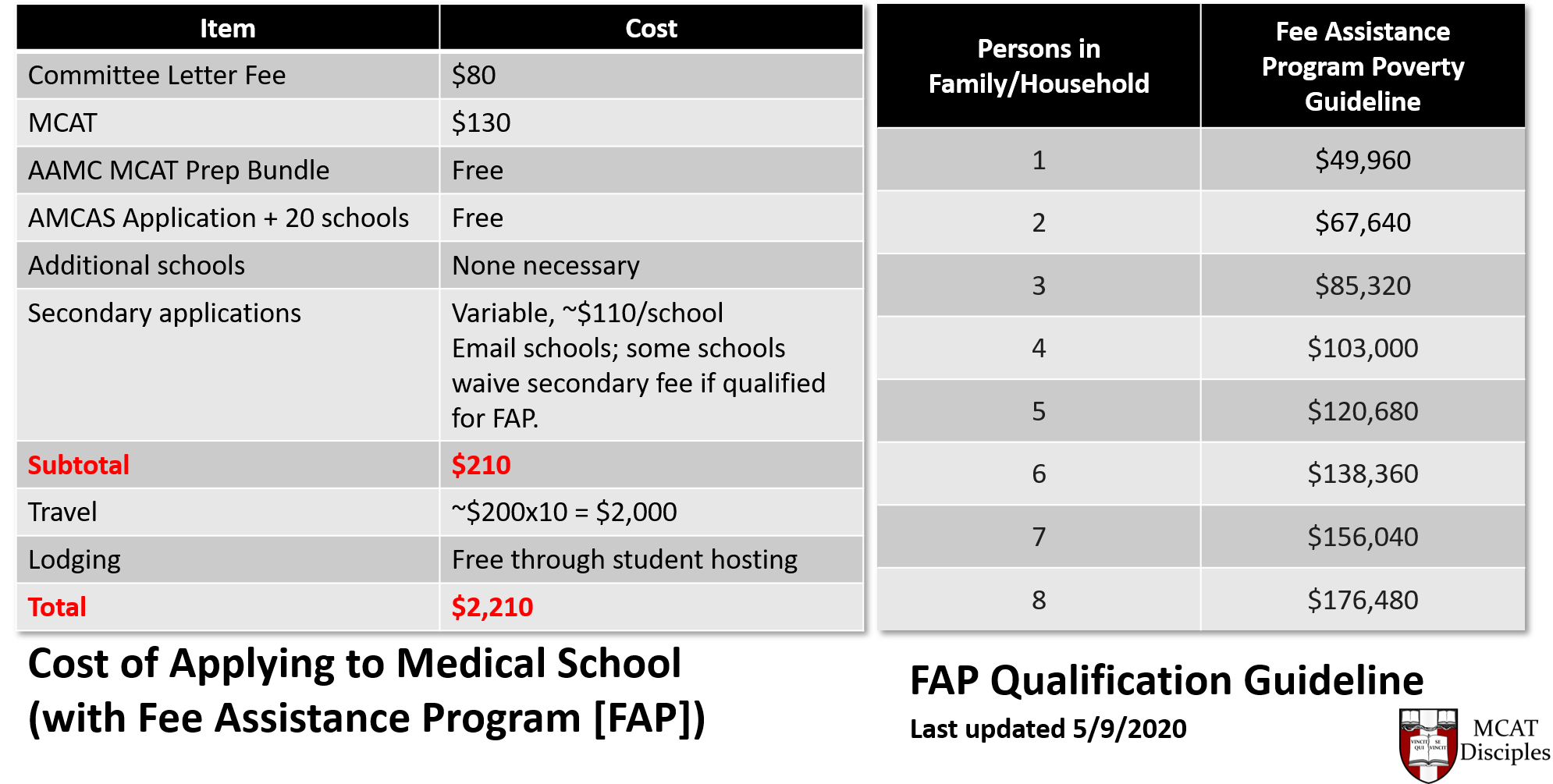

- Apply for the Fee Assistance Program (FAP);

- Through the AAMC to have some AMCAS application fees and secondary application fees waived.

- A good option for low income students; see below for income requirements and cost of applying to medical school with FAP.

- Winter/Spring/Summer of junior year: Study and take the MCAT; deadline to take the MCAT while being able to apply to all schools is September 15th of your junior year.

- Familiarize yourself with individual school requirements and admissions statistics.

- Continue with research

- Continue with volunteer activities

- Continue with clubs/interest groups

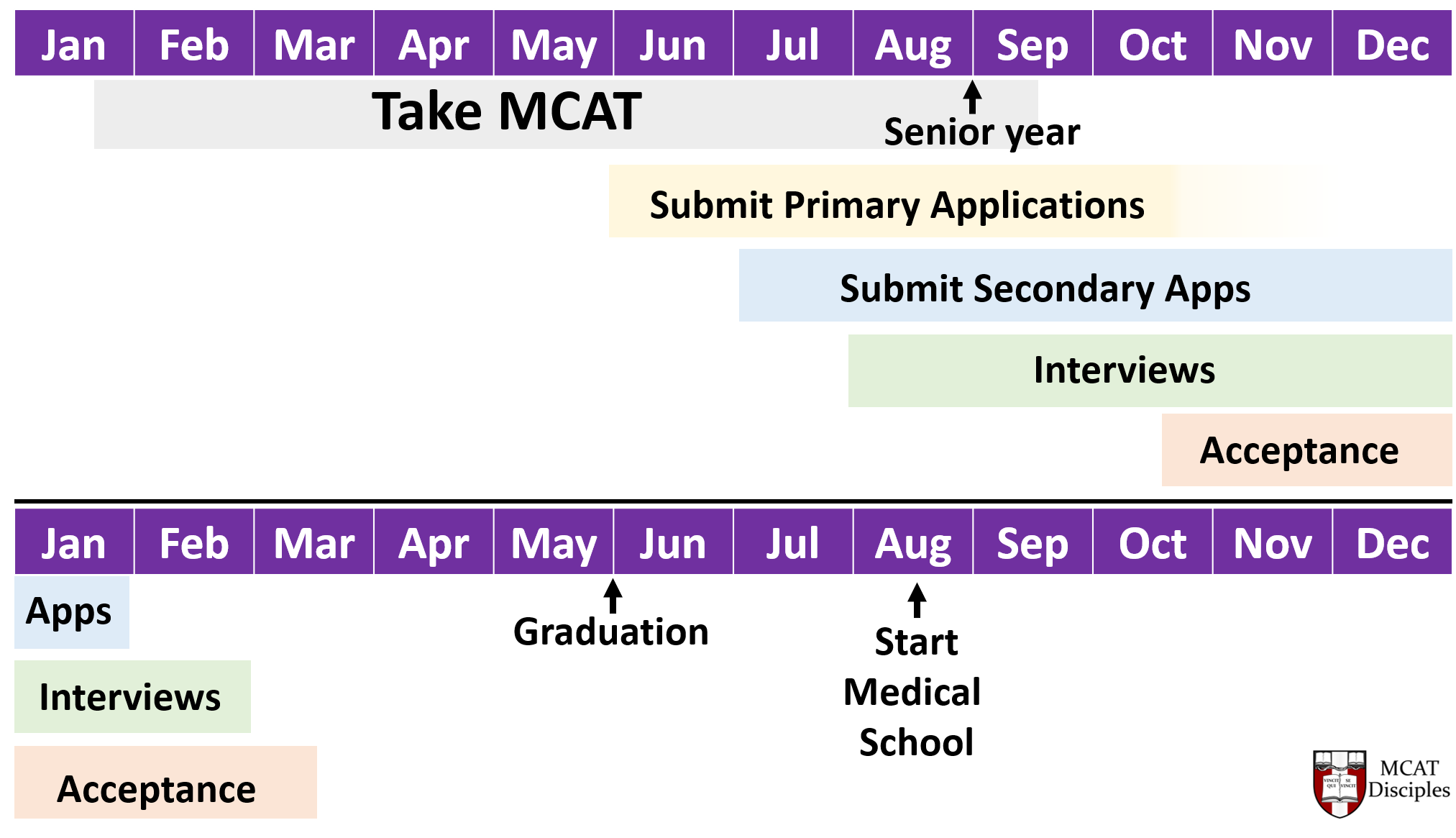

- See below for a time line on applying to medical school.

MEDICAL SCHOOL APPLICATION TIME LINE

COST OF APPLYING TO MEDICAL SCHOOL

Should I take a gap year(s)?

Taking a gap year or more is a personal decision. If you take 1 gap year, you will apply to medical school the summer after graduating and if taking two gap years you will apply the following summer.

Some things to keep in mind;

- If you take a gap year(s) you SHOULD plan to do something to strengthen your application

- Examples:

- Research year (paid or unpaid)

- Master’s degree (MPH, Master’s in Science, etc)

- Volunteer activities

- MCAT or work, AND one of the above

- It is OKAY to finish studying for the MCAT before engaging in the above!

Disclaimer:

Admissions committees will understand if you take time to work however, I HIGHLY recommend that you ALSO do research and volunteer. For some students prioritizing school, research, and volunteer activities is much harder than for others. However, it is very important that you have research and/or volunteer activities to make yourself competitive and to indicate to medical schools that entering medical school is a heartfelt goal of yours for the right reasons.

Trust that the resilience that brought you this far will carry you forward. With DACA or Undocumented status, it is important not to give admissions committees any reason to turn away from your application.

PRIMARY APPLICATION PROCESS (Spring/Summer)

PERSONAL STATEMENT (5,300 characters):

Your statement should be carefully worded and provide the reader with a window into who you are, why you are unique, what drives you, and why you came to medicine. It is an exercise in introspection and self-awareness.

- DOs:

- Committees look for;

- Personal commitment, integrity, and knowledge of the field

- Focus on something that is NOT already apparent from the rest of your application

- Show don’t tell; examples and detailed story telling are key

- Committees look for;

- DON’Ts:

- Focus on your family or mentors, they want to know about YOU

- List or summarize activities

- Disparage other doctors or professions (yes, this includes research)

- Make ANY grammar mistakes. Committees WILL notice.

- Use clichés

While this article provides sample DACA literary pieces at the bottom of this page, it is not meant to be comprehensive with regard to the AMCAS writing section; please refer to MCAT Disciples’ “AMCAS Prep Course” for more detailed information.

Should I talk about being DACAmented or Undocumented in my personal statement?

Although a personal decision and one not to take lightly, as a general rule you don’t want to mention something in your personal statement you are not prepared to discuss in an interview. Only talk about your status if it will strengthen your application and give reviewers a better grasp of who you are.

It may be that growing up undocumented influenced the way you viewed the world and inspired you to become a physician. In this case, it is something to talk about carefully. For example, you may want to show (not tell) how DACA made you a more resilient person but you do not want to go into politics, diminish the experience of others, or blame others (your parents). You have to keep in mind that you will have very conservative and very liberal physicians reading your personal statement. In America, hard work, resilience, perseverance, and social consciousness are deeply held values and that is true as well for many physicians.

NOTE: After you write your first draft, set it away for a day or two then return to it. Once you have edited once or twice, send to a trusted friend or mentor to review and make edits accordingly. You will likely go through several drafts before you have a final copy, could be as many as 30 drafts.

DISADVANTAGED STATEMENT:

Use this section to describe any additional challenges you may have faced. This is a place where you may want to mention your DACA or Undocumented status keeping in mind the same guiding principles as above in the personal statement section. I have attached a sample disadvantaged statement at the bottom of this article.

Letters of Recommendation (≥ 3 letters):

- 2 Faculty (Required)

- 2 letters – Professor in Biology, Chemistry, Mathematics, or Physics

- 1 - 2 Other: (1 Required)

- 1-2 letters – Any supervisor,educator, or doctor you’ve worked/volunteered with.

You should be requesting letters of recommendation shortly after or concurrently completing an experience or activity. If you wait too long, the letter writer may not remember you well enough to write a meaningful letter!

Committee Letter:

Most schools have an additional composite letter the school (health careers office) writes on your behalf. Generally this is a composite of all your other letters of recommendation. It is important that you learn about your school’s internal process. NOT obtaining a committee letter (if your school offers it) WILL put you at a disadvantage, and raises a red flag on your application. This process usually begins January of your junior year and the documents usually must be submitted by May 1st of your junior year, but check with your school for specific dates!

AMCAS Application Submission:

- AMCAS Application: Available May 1st

- Application submission: Opens May 31st

- Early Applicant: Submit within the first 2 weeks

- Late Applicant: Submit ASAP

- We would highly suggest submitting your application by ~the latest~ late July-early August

- The longer you wait, the less interview and acceptance seats are available to you, as many may have already gone to other students.

- Most students must balance taking extra time to get a better MCAT score vs applying later and potentially have less of chance of obtaining an interview based on numbers alone.

- I think that all (most) students should have at-least 1 month of dedicated MCAT preparation outside of the college classroom. If taking an extra month or two after May for MCAT preparation is going to mean a 5+ score bump of your MCAT score, and you’re confident that with more time you can achieve this increase to an otherwise uncompetitive score, I would suggest taking the time!

The average MCAT score for a Latino student entering allopathic (MD) medical school is a 503, or the 61st percentile.

SECONDARY APPLICATIONS

Each school that you apply to will send you a secondary application, which is usually 1-3 additional essays that are school specific and range from 250 to 10,000 characters, with the average being 3,000 characters. While these secondary essays can change per year, they usually do not, and so you would be wise to pre-write secondary essays before receiving the secondary application. The reason is this: if you do not pre-write, you will suddenly have 20+ essays to write, and the longer you take, the longer your application is sitting in the waiting station while other students are receiving interview invitations. Visit this website for a database on school-specific secondary essays.

- Upon receiving:

- Submit within ≤2 weeks

- The sooner the better

- It’s a way schools can gauge interest

- Fees:

- Some schools will waive fees if you are part of the Fee Assistance Program (FAP), but otherwise the average fee is approximately $110 per school.

Do I bring up DACA or being Undocumented in Secondary Applications?

The same guidelines used to decide whether to include in your personal statement apply here as well. See pertinent personal statement section above.

Should I apply to DO schools?

Speak to your advisors regarding this. Because your status will limit the number of allopathic schools you can apply to, you want to cast your net wide. It is better to apply to more schools and subsequently turn down interviews than to not apply to enough and be denied.

Which medical schools are DACA friendly?

This is a wonderful question, and I have made a comprehensive table as an answer to this question, which can be found at this link.

INTERVIEWS:

Interview invitations are rolling. You will generally receive about 2 weeks’ notice. The more you practice interviewing the better you will get. Practice with a friend or advisor several times. Even if you are a good interviewer, you can always be better. Make sure you loosely memorize some answers to the most common questions to make for a smoother interview day!

Interview formats:

- One-on-one interviews (traditional)

- Interview(s) with a faculty member or student

- Multiple Mini-Interviews (MMIs)

- Several stations where you will be asked to;

- Complete tasks, write, answer ethics questions, interact with standardized patients or an individual, or complete a series of interviews.

- Several stations where you will be asked to;

Remember, you will constantly be observed even when you think you are not.

Attire:

The attire is business; customarily men wear black suit pants, white button-up shirt, tie, black jacket, dress shoes, and are most often clean-shaven. Women customarily wear black pants and a white blouse. It may be tempting to wear heels but remember there is a lot of walking on tours. Do not stand out too much but also be yourself. Colorful socks are welcomed.

Travel:

Travel light and plan ahead for unexpected delays. Arrive the day before your interview and leave the day after. This will ensure you are nearby the night before your interview and allows for time to explore the surrounding community if you choose to attend.

Budget friendly advice: Staying with current students is the best budget-friendly option and a great way to get an inside look at the school and community values.

Interview day:

- Arrive early but not too early; 20 minutes is a good number

- Be friendly to other interviewees

- Assume you are being watched at all times

Should I disclose my status during my interview?

This is a personal choice and there is no right or wrong answer. Your AMCAS application will denote whether you have DACA or are Undocumented on the first page. This is a feature AAMC has added to applications in recent years to better track the number of DACA or Undocumented applicants. Your reviewer will be aware of your status if they are in a school where interviewers are allowed to see applications prior to interviews. There are schools however that are “blind” interviews which means the interviewer will not have seen your application prior to interviewing you.

If you mentioned your status in your AMCAS application anywhere besides the initial demographics section, it is likely the interviewer will ask you about it. In any case, you should be prepared to answer any questions the interviewer may ask. This is why doing mock interviews with advisors is very important as they can mimic some of the emotionally difficult questions you may be asked such as;

- Did your parents bring you here “illegally”

- What will you do if DACA goes away?

- How did you manage with the stress and uncertainty growing up?

- Would you ever like to practice in your “home” country?

- What will you do if you are unable to practice medicine in the United States?

- Do you miss your family and friends?

- Do you have any memories of your childhood in your country of birth?

In short, you should be prepared to answer any questions about your status in a composed and formal manner regardless of the content of the question. You are there to make a good impression however if you are asked heinous questions, you are free to take that into account when choosing where you will attend later. Regardless, you still want to make the best impression and composure is key.

Additionally, if you are not asked questions directly but feel that mentioning it when appropriate will add to your application and give reviewers a more holistic view; I would make sure to do so in a well-rehearsed and thoughtful manner.

ACCEPTANCES:

Congratulations! Take a moment to take it all in.

Depending on the school, you may not have to do anything else or you may have to submit a deposit to hold your spot. You are able to keep as many acceptances as you’d like until the last week of April, which is when according to AAMC guidelines you must drop all acceptances but one.

Prior to deciding, we highly suggest checking with each school’s financial aid office for DACA or Undocumented student financial aid options as they vary per school. Moreover, I would stay in close contact with the admissions office or office of diversity to ascertain that you can in fact matriculate at the school prior to making a final decision. There have been cases of students being accepted but not being able to matriculate due to internal or state rules that prohibit non-residents or non-citizens from enrolling. This is why it’s important to check with each school you are accepted to that you can in fact matriculate.

WAIT LISTS:

You can keep as many wait list spots past April and well into the summer. If you find that there is a school you would really like to attend, we advise sending a letter of intent. This is a letter that goes directly to the school and lets them know you will attend if you are accepted.

FINANCIAL AID:

- Pre-Health Dreamers Scholarship List

- MCAT Disciples Annual MCAT Scholarship Course for URMs in Medicine and Their Allies

SUMMER INTERNSHIPS: DACA/UNDOCUMENTED FRIENDLY

- Pre-Health Dreamers Internship List

OTHER DACA RESOURCES:

- Pre-Health Dreamers Resources

- MiMentor Physician Mentorship Organization

Sample DACA Writing Statements:

(SAMPLE) DACA PERSONAL STATEMENT:

It’s a cold New England Tuesday afternoon at Clinica Esperanza, a free clinic providing health care to the uninsured in Providence, Rhode Island. A middle-aged couple hands in their paperwork as the intake volunteer and I, the Spanish translator, guide them towards the intake room. We sit down and begin the intake process. First, we take anthropometric measurements before moving on to the social history questions. The questions become personal and the couple begins to speak about immigrating to the United States. With some hesitation they speak about not seeing a primary care physician in years due to lack of health insurance and their immigration status. As I translated, I remembered leaving friends and family in El Salvador, as my sister, mother and I embarked on a one-way flight to Maryland in 2001, when I was eight years old.

Moving on with social history questions, the couple is prompted to comment on their living situation. They disclose that they rent an apartment with relatives who also immigrated to the U.S. At this moment, I remembered the three months my family shared a room in an apartment and the basement we lived in for another three years. It wasn’t until 15 years later that my parents were able to live in a house. We continue the intake process with questions about their health status, which they joyfully attempt to answer in broken English. I recalled times when I accompanied my parents to free English classes on weekends and weekday nights at a local high school—a helpful compliment to the English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL) classes I was receiving at my Elementary School. Back at Clinica Esperanza, towards the end of the intake process, the woman asks me about my background, where I grew up, and where my parents reside.

My parents, sister, and I immigrated to the United States in search of opportunities and a safer environment than our violence-troubled country. From an early age, my mother taught me that hard work, a love for God, and caring for others is essential in order to contribute to society in a positive way. As I grew up, I came to the realization that exemplifying these values is not enough in a society where gender, skin color, and immigration status fuel prejudice and a cycle of poverty and disadvantage for those underrepresented. I learned that my uncle had not gone to a primary care physician in years due to lack of health insurance arising from his immigration status and that this was the norm for many adults in my community who were undocumented. I desperately wished there was something I could do for him and others like him who were kept from receiving this basic human need. During our first few years in the U.S, my mother took my sister and me to children’s free clinics for our annual physical examination. Doctors volunteering in these free clinics, who care for children like my sister and me, are part of my inspiration to become a physician. I am driven towards becoming a community-oriented doctor with an emphasis on serving the underserved. As a Christian, I am called to show love and grace to others regardless of their race, gender, ethnicity, and immigration status. As a future doctor, I hope to play a part in helping to improve doctor-patient communication by doing my best to try and understand a patient’s feelings, concerns, and experiences.

Back at Clinica Esperanza, the couple nears the end of the intake process. I converse with them as the intake volunteer completes their assessment. Soon after sharing that I emigrated to the U.S from El Salvador, they eagerly ask if I am a Dreamer—a term used for students with Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals status (DACA). Caught off guard by their question, I chose not to disclose this information. Growing up I was told by my parents “don’t tell anyone” concerning my immigration status. Reflecting back on the experience, I wish I had shared my experience of being an undocumented immigrant who was granted DACA status three years ago, thus allowing me to have a license that can be used for air travel within the U.S, a social security number, and a work permit. My immigration status has shaped the health care opportunities of my family and those around me. My hope is that the immigrant and underserved populations will feel comfortable sharing their stories as it pertains to their health. After all, societal factors affect our health and give rise to personal narratives that are invaluable to the care of a patient.

(SAMPLE) DACA DISADVANTAGED STATEMENT:

My family and I immigrated to the United States in 2001 from El Salvador with nothing more than a few suitcases and volumes of uncertainty. A few weeks after arriving we came to the realization that due to my undocumented status and my parents’ initial lack of a stable job, we were unable to obtain health insurance. While we eventually unearthed free clinics, finding quality education was the next hardship. Thankfully, my father became the maintenance worker and bus driver at St. Andrew's Episcopal School, a private school in Potomac, MD, that otherwise I would not have been able to attend. My mother works as a housekeeper and has done so since 2001 when we first moved to Maryland. In my growing years, my 4-person family lived in a two-bedroom apartment for 11 years and a one-bedroom basement prior to that. Prior to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) in 2012, I lacked the work permit and social security number that DACA now provides me with. It is due to this uncertainty: in finances, housing, healthcare, work, immigration status, and education, that I apply as disadvantaged to medical school.

CLOSING REMARKS

This was a lot of information and it is OKAY to be overwhelmed! Take a deep breath; you are resilient and have your community supporting you. Becoming a physician is no easy task, but you can do this because you are not alone! ¡Adelante!

Krissia Rivera Perla MD, MPH, Laureano Andrade Vicenty, MD

Krissia Rivera Perla MD, MPH, Laureano Andrade Vicenty, MD